The Grand Inquisitor of Toulouse

excerpt from The SECRET HISTORY of the WITCHES

© 2000 Max Dashu

Like many Dominican monks of his time, Bernard Gui rose through the ranks of the Inquisition. At the age of 35 he was named Grand Inquisitor of Toulouse, a repressive office he held from 1306 to 1323. The church hierarchy rewarded his efforts with a 1314 appointment as the Vicar of Toulouse, and he was sent on several papal missions to Italy and the French court. [Lea, Inq II, 104

Gui was a four-star general in the war on heresy. He wrote its principal battle plan, a handbook for Inquisitors entitled Practica Inquisitionis Hereticae Pravitatis: a "guide for inquiring into heretical depravity." A classic interrogatory manual of the medieval Inquisition, it detailed forbidden beliefs, practices and rituals, and set out formulas of abjuration to be repeated by those the Church Militant had tortured into submission. Interrogatory torments administered before the tribunal did not count as punishment, but as the means of extracting "confessions." Official penalties included death, imprisonment, exile, confiscation of property, and enforced pilgrimage to distant sites.

Gui authorizied inquisitors to proceed against heretics, "sorcerers," Jews who had submitted to forced baptism, and "against all those who oppose themselves to the Office of the Inquisition." Most of the Practica was aimed against heterodox christians: Cathars, Waldenses, Béguines, "False Apostles." It recognized the upsurge of resistence to the institutional church, which Gui blamed in part on kings interfering with the Inquisition. [Lea II, 104]

His manual directed special venom against Jewish converts who had returned to their people, who threatened the clergy's cherished notions of christianity's superiority. The French inquisitor compared these Jews to "dogs returning to their vomit," a slam that had originated in the pogroms of the First Crusade. In those days, when Jews forced into baptism at sword-point refused to adopt their oppressors' religion, the chronicler Fruitolf wrote that they returned to Judaism "even as dogs return to their own vomit." [Poliakov I, 51] Like his colleagues, Gui slandered Judaism as "perfidy" and "intolerable blasphemy." He condemned Hebrew prayerbooks and the "Talmutz," claiming that they contained "imprecations and curses that Jews make against christian people." [Practica, 291] His claim that Jews prayed for god to destroy the Roman faith and all christians was a projection of the priesthood's desire to crush Judaism and the chronic violence that christians committed against Jews.

The final section of the Practica is directed against witches, or as Gui put it, "Sorcerers and diviners and invokers of demons." This document proves that Inquisitors concerned themselves with folk witchcraft at an early date, 165 years before the Malleus Maleficarum was published. Yet historians have repeatedly passed over this significant nugget and ignored its implications. [Lea probably did not recognize the significance of the folkloric references; Russell, 174-5, mentions it briefly, but does not describe its pagan contents, which refute his thesis that paganism had been suppressed by 1000.]

Most historians have accepted the diabolist conception of witches, searching everywhere for women who did evil and had intercourse with devils. They tried to match early records with the satanic stereotype of the mass burnings, and failing to find anything, declared various dates as the definitive horizon of the witch's appearance in Europe. (The definition of witch they had in mind was the diabolist stereotype.) Some stated categorically that no evidence of "true" witchcraft was to be found before 1400, when demonological tracts began to be widely circulated and pronouncements by church officials against witches stepped up.

All this time, the historians ignored crucial testimony that placed witchcraft's roots in folk culture. The evidence was not hidden in some long-lost manuscript, but in the often-cited Practica of Bernard Gui. His description of "sorcerers" contains no mention of devil-sex, but lists faery beliefs and folk rituals similar to those found in medieval literature and modern peasant folklore.

The "sorcerers" of the Practica are not the destroyers and blight-casters found in 16th century trials. They are not accused of the baby-eating atrocities propagandized by witch-hunting Inquisitors a century or more after Gui's time. The "sorcerers" of this fourteenth-century Inquisitor follow primordial Pagan beliefs in the fatae: "the weirding-women, called the good ones who, as they say, go by night." [de fatis mulieribus quas vocant bonas res que, ut dicunt, vadunt de nocte [Practica, 292]

Gui was well aware that the mysteries of the faery religion still held power for the peasantry, especially for women. Sorcières who chanted over herbs and cured with conjurations of the fadas or foxileiros acted as priestesses in fundamental ways that ran deep in popular culture. They presented a challenge to ecclesiastical doctrine that was even more broad-based than that posed by the heretics.

The old spirituality was more favorable toward women than institutional christianity. The authoritarian church reserved its own priesthood to a male elite, who received financial and legal benefits from their membership. Even village priests had privileges and immunity from prosecution by the secular power. Priestly offenders, whether adulterers, rapists, or magicians, were dealt with by the church alone, and treated far more leniently than farmers and fishwives, in the unusual event that they faced any disciplinary action. This special legal treatment mirrored the privileges of aristocrats and men as against commoners and women under feudalism.

Gui's manual gave great weight to the gender of the person who was being cross-examined for "sorcery". He advised interrogators to considerthe quality and condition of the persons, who are not to be interrogated equally or in the same way for everyone, because men are cross-examined in one way and women in another.

This revealing comment stops short of spelling out the difference in how the brotherhood of Inquisitors treated men and women. A look at church precedent offers a dismally uniform bias favoring the male and restraining females. But there is more to Gui's emphasis on gender difference: he assumed that his reader knew what acts women performed that men did not do, ritual acts which were culturally female, handed down and performed by women. The inquisitor broke down "sorcery" into two distinct lists that clarify his meaning. The first sequence concerns witchcraft of the common woman, the second deals with priestly sorcery based on christian sacraments.

WOMEN'S RITES, NOW "SORCERY"

Gui's description of folk sorcery, though succinct, covers a wide range of beliefs and practices: the prophetic women who go by night, fate-foretelling for infants, ritual chant, conception magic and the witchcrafts of love and marriage, all explicitly identified as women's realm by medieval sources. The inquisitor's list is fragmented, disjointed, not showing the relationship between its parts, or the meaning of those parts. Its succinctness reflects an expectation that interrogators were familiar with popular animist culture.

The unmistakable shadow of fates and faeries is reflected in Gui's terse catalog of sorceries. The Practica shows that in Languedoc of 1320, women carried out fate-divination and child-blessing rites on their own, bypassing the priesthood. The common sorcières addressed their incantations to immanent goddesses of destiny, not to a christian Demon.

Women's rites of birth head the list of sorceries. The Inquisitor begins by asking what the accused knows, or knew, or did, with regard to the fating or the unwinding of fate for children or infants. [fatatis seu defatandis] Next the interrogator asks about souls having been lost; here we are certainly looking at shamanic concepts of "soul-loss" as a cause of illness, not the christian notion of damnation. In the same way, heaven or hell may have had less to do with the author's inclusion of the condition of the souls of the dead than with the journey of souls to the Otherworld, and ancestor cults of ancient vintage. Communion with the spirits of the dead, and relaying messages from them, was a classic power of the European witch. Peasant tradition held that the dead could be sighted journeying with the Old Goddess on the Ember Nights. A line later, Gui underlines this connection by specifying the weirding-women called the good ones, who as they say, go by night.

Inquisitor Gui asks further what the accused knew about or might have done regarding the pronouncement of future events and enchanting or conjuring fruit, herbs, thongs, and other things. The enchantment of thongs refers to the witchcraft of knots. The practice of singing incantations over herbs is attested in the oldest records of Pagan observances. The Inquisitor lingers on this subject of the chant used in healing, and its transmission from woman to woman. He demands from the sorciere the names of those whom she taught chanting or to conjure by chanting, and from whom she learned such incantations for conjurations. Also forbidden are curing the sick by conjurations or by chanted words and bringing about impregnation of women. Conception magic!

Even christianized practices such as collecting herbs with the knee bent and the face toward the east with the lord's prayer are here considered sorcery, along with the combination of pilgrimages and masses and offering candles and giving alms. The peasantry still understood religious acts--including christianized ones--as generating power to achieve desired aims. Lighting a candle in a faery grotto could bring about healing or recovery of a loved one. While the "good women" smiled on these offerings, theologians considered them heretical attempts to coerce god, even with masses and lord's prayers thrown in. Few peasants were foolhardy enough to admit to the Dominicans that they invoked the spirits of herbs or waters or the earth. And nothing could smack more strongly of witchcraft than discovering hidden facts or manifesting secret things.

Gui lists several sorceries aimed at relations between people. Thieves kept under restraint refers to spells intended to prevent theft or recover lost goods, attested elsewhere in European witchcraft literature. Concord or discord of married couplescovers an area of far-reaching concern to women, since husbands were legally defined as their lords and masters, entitled to beat them, cheat on them and squander their property. Witchcraft had long been considered the female remedy to this patriarchal status quo. In the 1300s, sorcery prosecutions were increasingly directed against women for using sorcery to stop their husbands from battering them, or to cause them to return home, or just because.

Out of all the "sorceries" listed in the Inquisitor's handbook, only two bear any conceivable relation to harmful maleficia. “Discord of married couples” might be a goal of amorous or jealous third parties, as easily a wife's spell to avoid intercourse or battery. Those who give to be consumed hair and fingernails and many other things could refer to harmful sorcery against a person whose trimmings were taken. Such practices are known worldwide, but so is the custom of destroy clippings to prevent others from stealing them in order to cast spells on them. The wording "give to be consumed" suggests that these remnants may have been thrown into a fire to prevent sorcery. Another possibility is that animist ancestor magic was involved. Inquisitors trying Cathars at nearby Pamiers uncovered a custom of cutting a dead person's hair and nails in order to bring happiness into homes. The same inquisitors also tried four women for invoking the dead. [Cauzons, 333]

HARMFUL SORCERY

It is crucial to distinguish between maleficia (the Latin name for evildoing sorcery) and the vast body of pagan culture, including ancestor veneration, which churchmen insisted on defining as diabolical. Every shamanic and aboriginal culture believes in the possibility of malicious sorcery, and Europe was no exception. But the priesthood refused to make a distinction between shamanic healing and malicious sorcery.

Doctrinally, female witchcraft was taboo and male magic was... religion. According to theologians, only males could perform sacraments. Under the new order, to act as a priestess meant that a woman could be accused of sorcery. Conversely, if a priest’s “magic” fails, he has not failed; it must have been the will of god. In spite of early medieval stories that describe priests vanquishing pagan rivals, over time the Church hedged away from any proofs of effectiveness such as those commonly displayed by shamans. [Herbert Frey, “Religion as an ideology of domination,” in Bak, Janos M. and Gerhard Benecke, Religion and Rural Revolt, Manchester U Press, 1984] Although doctrine cast the witch as an evil curser, the clergy evolved its own formulas for cursing—anathemas, excommunications, denial of sacraments. Pronouncing these curses was supposed to close off access to the divine and, unless they were lifted, to doom the victims to eternal hellfire.

The old animist world view allowed for the possibility that curses could be laid, that harm could be done to someone through manipulation of symbols or dust from their footprints or a lock of their hair, or even through malevolent looks and speech. It also provided animist rituals that protected against such action, through which deities and natural powers could be brought to bear on a person's behalf. Remedies existed in the form of artemisia and south-running water and holy stones, rowan twigs and red thread.

Societies that recognize the powers of shamans also take into account the possibility of their misuse. Those foolish enough to desecrate medicine powers were capable of using them to do harm through sorcery. The Saami, for instance, considered most noaidis (shamans) to be beneficent but acknowledged occasional cases of evil-doers. [Karsten, 68] Finns also spoke of "noaidi's arrows" being used to harm. Some Norse sorcerers sent out spirits called sendingar or stefnivargar ("directed wolf") or "mice-wolves," to injure enemies. Others sent spectral milk-hares to bring back cream from others' cows. [Craigie] Belief in this magical theft of milk or milk-essence went back centuries and was known across Europe.It was this type of accusation—not diabolism—that dominated peasant thinking when witch-hunting began to penetrate the villages as a tool of communal strife.

But the old folk cultures held that there were natural controls on magical evildoers. Traditional wisdom warned of the three- or sevenfold return of any wrongful act of sorcery:The belief among the ancient Irish was, and still is, that a curse once pronounced must fall in some direction. If it has been deserved by him on whom it is pronounced, it will fall upon him sooner or later, but if it has not, then it will return upon the person who pronounced it. They compare it to a wedge with which a woodman cleaveth timber. If it has room to go, it will go, and cleave the wood; but if it has not, it will fly out and strike the woodman himself, who is driving it, between the eyes. [O'Donovan, in Wood-Martin, Pagan Ireland, 149]

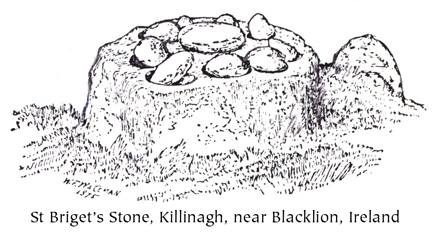

Certain power places were resorted to by people who had been injured to cry for retribution. "If a widow or other wronged person made a curse while turning a cursing stone against the sun, it would plague the oppressor's family down seven generations." [Merle Severy, "The Celts: Europe's Founders", Nat Geo vol 151, #5, 1977] People came to St Brigit's Stone near Lough Macnean in Ireland, a flat-topped boulder with nine dents containing smooth oval stones, to turn the stones while cursing. [Wood-Martin, 150] So some of these customs became christianized.

A religious context for cursing may seem paradoxical (especially given the unshakably beneficent nature of the goddess Brigid in Irish culture), unless it is understood as an appeal for justice. Its execution is left to the goddess. This concept of appealing to the deity to punish wrongdoers is not foreign to the Hebrew scriptures.

The Catholic priesthood devised its own protocols of cursing on religious grounds. In excommunication, the priest formally cursed those he was casting out of the church, fully believing that he was condemning them to eternal hellfire. In animist terms, declaring that someone will go to hell or calling down a god's displeasure is nothing if not a curse. Many women were burned as witches for predicting much less fearful outcomes. Early church patriarchs were not averse to cursing even christians who disagreed with them. Bishops Cyprian and Gregory of Nazianzus, for example, “called down God’s vengeance against Christians who disobeyed their leaders.” [Lane, 543]

In the rite of excommunication, church officials in full regalia carried candles in procession to the altar, singing softly as a priest called down curses on the excommunicates: "May the wrath and damnation of God Almighty come upon them..." The officiant invoked Mary and all the saints, asking that the excommunicates suffer all the plagues of Egypt and the misfortunes of Sodom and Gomorrah.Their food and drink, their waking and sleeping, shall be damned... They will lose their court cases and their days shall be numbered and evil. They shall forfeit their goods and property to others. Their children shall be orphans and always in want. Fire shall reduce them to penury and wheresoever they shall turn their steps they will be met with abhorrence and shown no pity. [Henningsen, 100-1]

Then the priests consigned their victims to the devil. The assembled clergy all quenched their candles in holy water, saying, "As these candles die in this water, so shall the souls of these rebellious and obstinate people die and be buried in Hell." [The printed Anathema de Valladolid, early 1600s, in Henningsen, 100-1] More than this, the priesthood demanded that people attend these terrifying displays of hatred, to make the curse take hold in the collective mind.

Folk ways of dealing with cursing and sorcery were milder. It was common practice to get a suspected sorcerer to simply say a blessing over the alleged victim. [deWaardt, G-H/F, 137] Even the demonologist Rém reports a peasant custom in Lorraine: when someone gets sick from an unknown cause, he goes to the person he blames for it, and get something to eat or drink “in the greatest confidence that it will restore him to health.” [Horsley, 184]

In Germany, Franconian witch belief interpreted witchcraft as a response to wrongs or offenses. It seems as if the hex was often understood as the negative consequences of bad feeling rather than a conscious act of witchcraft. If someone was afflicted with lice, for example, they should go to the person they believed was responsible for the curse and beg their forgiveness for whatever had offended them--the theft of fruit or hay, or allowing their cattle to roam into a neighbor's field. This custom of Abbitte was followed in many cases to try to lift hexes. [Sebald, 77, 104]

This was how the "evil eye" was usually interpreted. The life-force of a wronged person could be shaped by their rage and pain without intention to work magical harm. The Italian custom of making "horns,” or “the fig,” was a popular warding gesture that was considered protective magic. Highland Scots used to wind black and white thread around limbs of anyone, human or animal, believed to have suffered the evil eye. [CL Day, 41] These remedies originally were religious and ritual in character. But evil eye beliefs grew deadlier in the witch-hunt era, as poor/disabled/old/women came to be targeted as its probable source. The evil eye was refined into a weapon against female elders, the disabled, and the defiant poor.

People in animist cultures all over the world had traditional methods of recourse against harmful sorcery. But in medieval Europe the remedies themselves were doctrinally redefined as sorcery, even though the Church's own holy water, incense, and blessed oils grew out of these same animist roots. Priestcraft destroyed traditional distinctions between shamans and cursers, between inspired trance and involuntary possession by malevolent powers.

It was because folk rites and divination and curing were grounded in goddess veneration that the Church denied their religious nature. The shamanic healers and diviners consulted in illness or misfortune were not only outlawed as competitors to the official priesthood, but treated as harm-doers and public enemies. As the witch hunters gained the upper hand, they succeeded in replacing the Old Goddess with the christian devil.

CLERIC-MAGICIANS

The second category of sorcery described in the Practica was based on belief in the power of Catholic ceremonial. The practice of using Catholic sacraments and lituries for magical purposes was becoming popular among renegade clerics. Priests would consecrate wafers or chrism or water with the Latin liturgy, or baptized images of wax or lead for magical uses. The Practica was written at a time when many clergymen had become involved in ceremonial magic, invoking angels and devils with biblical names in Latin or Greek formulas. These practices were not new. As early as 694, the 17th Council of Toledo decreed punishments for priests who celebrated funeral masses for people they wanted to kill. This practice lived on and was repeatedly condemned, for the 15th time by the bishop of Cuenca. [find source, 444]

The priesthood believed in the demons of the christian patriarchs. From the time of Dominic and Aquinas on, clergymen had grown increasingly involved in ceremonial magic. Church records and correspondence show that many clerics were involved in sorcery based on misusing the christian sacraments. [McCullogh] Scholarly sources name only educated men as "high magicians." Spain, especially Toledo and Salamanca, was the center for churchly magicians. [Menendez-Pelayo I, 597ff] The University of Toledo even offered a degree in magic arts. The bishop of Lerida was a famous magician who wrote a book on sorcery and how to undo maleficia. Pedro Muñoz, the archbishop of Santiago, had become such a notorious necromancer that the pope ordered him to be immured in a hermitage. [Lea 455]

But abbots and monks frequently practiced magic themselves, or accused each other of it. Various church councils addressed the epidemic of priestly magic by calling for excommunications. [Lea 422-3, 455] In 1220 the necromancies of the archbishop of Santiago, Pedro Muñoz, were so notorious that pope Honorius III had him confined to the hermitage of San Lorenzo. [Lea, 429] Even popes were said to be sorcerers or "high magicians." Gregory VIII was one such sorcerer-pope. John XXII employed magicians as well as persecuting them. The church generally was very lenient with priest-magicians; often the penalty was degradation from orders, or being sent to a monastery. Occasionally kings trumped up charges against popes during political power struggles; Philip IV of France called an assembly in the Louvre to charge Boniface VIII with keeping a familiar demon and consulting diviners. [Lea, 451]

Some of these learned sorcerers got involved in some grisly deeds. Italian physician Francesco di Sandro was caught leaving a cemetery with a dead man’s severed head, which he told judges he planned to use for prognostications. His punishment of four years of jail was much more lenient than the usual. The judge took account of his rank, “desiring by means of gentle correction to lead onto the path of safety.” In another case, Niccolo Consigli was undaunted by several trials for sorcery, excommunication, and years on the run; at last he was captured and sentenced to death, but even then the bishop and clergy opposed his execution. [Brucker, 134, 129]

Many leading university scholars of the 1300s became obsessed with the doings of demons. We could attribute this to the potent influence of Dominicans and Franciscans who had flocked to the universities and made their mark on the theology expounded there. These two monastic orders had become the watchdogs of dogmatic purity who, between them, ran the Inquisition. It was the Dominicans who shaped the doctrine of satanism which would provide the pretext for witch hunts up to modern times. The key players in the diabolist persecutions of the early 1200s—pope Gregory IX, Conrad of Marburg, Conrad Tors, Bernard de Caux, Etienne de Bourbon— were all Dominican monks.

But the persecution of witches remained a low priority in the Inquisition's first century. In Gui's time, diabolism was in ferment, but had not yet been tapped as a strategic weapon against witches. Likewise, there is no evidence that the folk practices being targeted by the Toulouse Inquisition were yet being punished with severe penalties such as burning. Public humiliation seems to have been the preferred method in this period.

Gui touches on diabolist themes in relation to "conjurers, charmers and necromancers," who are to be punished by wearing on their clothing ymagines seu figuras ymaginum de filtro crocei coloris. He describes them as bleeding from some part of their body—a claim regularly made against Jews, as part of the rationale of the blood libel—and as mixing the blood with toad blood as a sacrifice to the devil. [Delpech, SdS?, 356]

The outstanding qualities in Gui’s catalog of folk witchcraft are prophecy and divination, healing, and shamanic chant. Magic of conception and sexual politics appear as they had in the old penitential books. The witchcraft of herbs is mentioned twice. The inquisitor systematically moves down his list, cross-examining the accused on each forbidden subject, the belief in fateful women, clairvoyance, incantation, communion with the dead. He asks not only if the accused practiced these forms of witchcraft, but from whom she learned them and to whom she passed them on. The priesthood was actively striving to wipe out the transmission of this culture.

The deep secret of witchcraft literature is that in European folk culture witches were connected with shamanic practices and goddesses. Even their enemy, the Grand Inquisitor of Toulouse, does not yet claim that the sorcieres curse and blast. He describes acts historically associated with shamans and priestesses, toward the end of wiping them out their spiritual practices. His successors became more devious, inventing horrendous stories to turn people against the sorcières themselves.

PAGANS ON TRIAL

Old ethnic traditions were strongest among the peasantry who lived closest to the land, especially those inhabiting wilderness districts out of convenient reach of the feudal church and state. There, people were animists, celebrants of Nature sacraments, and nominal christians. Though they suffered their children to be baptised or yielded to the priesthood's incessant campaigning to get them to come to Mass once a year, the countryfolk had not abandoned their springs and groves, their May dances and Midsummer bonfires and Ember Night offerings to the Old Goddess.

Pope Benedict XII, called the "scourge of the heretics," had a record of repressing heresy and sorcery as bishop of Pamiers. His zealous attempts to stamp out pagan practices—defined as "sorcery"—found a wider scope when he became pope. He ordered church and state officials of all localities "to inquire and proceed against all persons defamed or denounced for heresy, schism, sorcery or other crimes against the faith, with all the privileges of the Inquisition..." [Vatican Archives, in Lea, 222].

While Benedict sat on the papal throne (1334-42), he personally supervised the trials of a number of accused sorcerers from France, Italy and England, ordering payment for informers and messengers from Vatican funds. (Many of these defendants were clerics involved in magic, or accused of it.) Payments went to Foulques Peyrier, the notary of Cahors, for recording numerous sorcery trials, [Cauzons, 360] The pope blessed the feudal official Gaston de Foix for arresting two sorcerers in Béarn, and had them tried and punished in Avignon. [Lea, 222]

Priestly sorcery was not the only variety under the pope's scrutiny. In 1338 Benedict tried two peasant women of the Vivarais region for congress with demons. Catharina Andrieva and Simona Ginota stood accused of having paid an annual tribute of wheat "to the devil," along with other "superstitious and damnable words and acts." This wheat was probably a harvest offering to the Earth or to the "good women." In any case, 14th-century Vatican sources are telling us that women publicly officiated in a forbidden agricultural ceremony. The pope had Catharina and Simona punished, but the penalty was not recorded.

The women's grain offering was likely to have been a corn granny woven from the first or last sheaf harvested, a longstanding peasant custom practiced all over Europe. (Hundreds of examples can be found in Grimm, Fraser, and other folklore sources.) German farmers used to rake up a small pile of hay to be left as "the wood-maiden's due." Offerings to this wild, shaggy, moss-covered forest goddess were general over much of central Europe. It was customary to plait an offering of grain or flax to her; sometimes a rhymed verse was recited over it. [Grimm, 1427, 1406]

In northern Germany, rye-mowers let some grain stand, tying it up with flowers. After harvesting the rest, they laid hands on this clump and shouted three times: "Lady Gaue, keep you some fodder, this year on the wagon, next year on the wheelbarrow." In the Prignitz region people called this reserved grain "lady Gode's portion bunch." [Grimm, 1009, compares these offerings to the Old Saxon deoflum geldan (devil's gold) in Leges Wihtraedi 13]

Gaue or Gode tied in with Hölle and Perchta and the other witch goddesses who presided over the shamanic hosts. As it became riskier to uphold these traditions, some people continued to observe them surreptitiously. In early modern times, christianized peasants began to chivvy others who kept alive such heathen ways. In Hameln, it became customary to mock peasants who seemed to pass over a section of grain: "Is that for Fru Gaue?" [Grimm, 253-4] Thus pressure was brought to bear on people who observed pagan agricultural rites and customs.

Those observances were no longer universal as they had been in past centuries, but they were still well-known to everyone. Gradually they were worked into the emerging diabolist doctrine and the witch hunts. Two centuries after the pope prosecuted Catherina and Simona for their wheat offerings, an accused Slovenian striga was charged with taking the form of a gander to gather up the crop (1532). She stood accused of giving the grain to the "evil spirit" on Whitsuntide, an important faery holiday in southeast Austria. [Pocs, 85]

The Inquisition's expansion into witch trials was an uneven process, driven by the penetration of diabolist doctrine. In Italy around 1350, the bishop and inquisitor of Novara consulted a legal expert about the proper sentence for a witch. They had convicted a woman from Orta of adoring a demon and killing babies. The mothers testified that she had bewitched them by touching them. The eminent professor Bartolo da Sassoferrato was of the opinion that death was a suitable penalty, citing a law that witches “should undergo extreme torture and be burned in the fire.” In the next breath, he counseled them to torture the woman and confiscate her goods, but spare her life. But the bishop and inquisitor should do as they thought best. They put the woman to death. [Bonomo, 133-4] This represents a turning point when torture and the death penalty begin to mount, the genesis of the mass hunts to come.THE INQUISITOR OF ARAGON

Toward the end of the 1300s a rising wave of witch inquisitions swept over western Europe. The popes' reluctance to allow Inquisitors to stage witch trials had been replaced with deadly zeal In 1374, when the Inquisitor of France asked the pope for the authority to deal with sorcery cases, Gregory XI urged him to prosecute them with all speed. Even earlier, Inquisitors carried out witch trials at Agen, France, in 1326 and in Como, Italy, in the 1360s, targetting a secta strigarum (“sect of [female] witches”). There were also a group trial at Siena in 1383; the trials of goddess worshippers at Milano in 1384-90 (see below); the trials of “vaudois” (a name that had meant “heretic” but was transmogrifying into a new diabolized meaning of “witch”) for devilish assemblies in 1387-8; and some unrecorded trials in the north and west of Germany by roving inquisitors in the late 1300s. [Kieckhefer, wc]

As we have seen in an earlier chapter, theologians had broadened the definition of sorcery to include the worship of outlawed deities. More and more, inquisitors focused their attention on people—especially women—who took part in pagan rites. After 1330 the early papal Inquisition in Spain dealt with cases of magic, sorcery, and superstition. [Llorente, 300] These inquisitors took a demonological tack toward popular spiritual practices, especially in Aragón where the diabolist influence from Languedoc was strong. The year that Bernard Gui wrote his inquisitorial manual, Nicholas Eymeric was born in Cataluña. Soon, as a Dominican inquisitor, Eymeric took up Gui's condemnation of women's chants and rituals.

In 1357 Eymeric was appointed as Grand Inquisitor of Aragon, a position that earned him the sincere hatred of the common people. He was not the only one. Inquisitor Ponce de Blanes was poisoned and his colleague Bernardo Travasser was assassinated for crimes in the service of the Holy Office of the Inquisition. Opposition to Eymeric himself was so great that he was removed from his position in 1360, a rare concession from the Inquisition. It proved to be a temporary tactical move. Within six years Eymeric was back in power.

On his return he published a treatise (1369) aimed against people who invoked “demons." His Directorium Inquisitorium (1376) pursued the same theme “after many more years of experience,” as Baroja delicately put it. This manual identified three kinds of sorcery, which all boiled down to worship of forbidden deities:I. Eymeric condemned people who praised and sang songs in honor of “the demon.” Where did these songs come from, if not from folk tradition? It was not the style of scholastic “high magicians” to sing prayers to the spirits they summoned with such grave Latinate ceremony. When theologians spoke of the veneration of “demons,” they meant the people's divinities. The songs were seasonal carols and chants invoking the old deities, which Eymeric collapsed, as doctrine demanded, into a single, male devil.

They worship him by signs and characters and unknown names. They burn candles or incense to him or aromatic spices. [Kors, Peters]

II. Eymeric despised these "sorcerers," not for atheism or for causing harm, but because of their religious beliefs. They “insert in their wicked prayers the names of demons along with those of the Blessed or the Saints.” Here the old belief is forced into the mold of diabolism even when it assimilates to catholicism.

III. The Aragon inquisitor denounced ceremonies in which a circle was cast on the ground with invocations, and a child placed in it, or a mirror, a jar of water, or writings. Now Eymeric reveals who it was that performed these unauthorized rituals:

And from this it appears that the said evil women, persevering in their wickedness, have departed from the right way and the faith, and the devils delude them. [Kors & Peters; Baroja; Lower]

As in Gui's manual, women acting as priestesses are attacked for “wrong” belief and “wrong” customs of worship: those which do not conform to church doctrine. It is not a question of Eymeric copying from the work of the Toulouse Inquisitor; the particulars are different. And Eymeric was more theoretical than Gui; he revealed much less about the practices he was describing. The trend in demonology was away from matter-of-fact description, and toward doctrinal claims of satanism.

Eymeric still took pains to make distinctions between sorcery that was heretical and sorcery that was not heretical, a pressing concern of Inquisitors before 1400. Not surprisingly, common enchantresses fared less well on this score than cleric-magicians. Eymeric thought it was not so bad to command the devil to do things which fell into his natural sphere, such as tempting a woman to have sex with the magician, because god had given Satan the power of temptation. But anyone who asked or implored spirits to heal, bless, or bring rain was guilty of heresy because this was like praying to “devils.” [Baroja, 92] This reasoning proved extremely popular; the Italian Inquisitor Bernardo di Como repeated it a century later. [Lea, 436]

In several cases, the Inquisition tried Spanish Jews for sorcery. Mosse Porpoler of Valencia had to pay a fine for magic in 1352. Inquisitors tried three Jewish women for witchcraft later in the century. They had attempted to recover stolen goods by "reeling off thread through the streets of the Jewish quarter... and concealing their threads at the entrance to the synagogue and in the Jewish slaughterhouse." These woemn were also accused of kidnaping and other crimes. Apparently their conviction caused some scandal, because the king reversed it. [Trachtenberg, 81-2. He fails to show his usual sympathy for the accused, writing "the ladies were probably guilty as charged."]

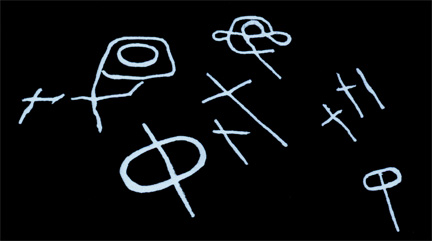

Inscription on the "Witches' Stone" at Sabassona, Cataluña

The Aragon Inquisition also oversaw witch trials in the province of Cataluña. It was supported by the local aristocracy and resisted by the peasantry. Catalan folklore kept alive stories about the Witches' Stone at Sabassona (la Pedra de les Bruixes), a boulder deeply engraved with ancient signs:

These indecipherable symbols have been attributed by popular tradition to the revenge of witches, who thus attempted to embarrass the feudal lord, who had close ties with the Inquisition according to the legend. [Mitos e Credenzas Catalanes, 66]

THE SOCIETY OF DIANA

An unknown number of commoners were tried for attending pagan gatherings in northern Italy. From at least 1370 to 1390 the Milanese Inquisition tried peasant women as witches for participating in the “society of Diana." The fragmentary nature of the trial transcripts indicate that parts of it have been destroyed or lost. [Bonomo; Ginsburg II; Evans; Cohn]

In 1384 a woman with the pagan name Sibillia was made to testify about “heretical” religious gatherings that amounted to paganism. She reported that she went every Thursday night to the "good society" to pay reverence to Signora Oriente ("Lady East"). The goddess prophesied future events and revealed hidden secrets to her company. They passed her teachings on to others. Sibillia said that all kinds of animals attended these gatherings, except the ass, which was marked with a cross. She said that the witches' society feasted on meat, and that Oriente had the power to bring the animals they had eaten back to life. [Bonomo, 16]

When the inquisitors inquired why Sibillia had never told her confessor about these gatherings, she replied that she did not believe them to be sinful. The chasm between the "witch" and her interrogators was unbreachable. In the eyes of inquisitor Ruggero, Sibillia was guilty of "enormous crimes." [Gii, 92] The inquisitors admonished their prisoner that she was guilty of mortal sins, penanced her, and then sent her home to Vicomercato.

Six years later the Inquisition arrested Sibillia again on the same charges. She still insisted that her activities were not sinful. She told the Inquisitors that at the end of her childhood she went to the games of Diana “whom they call Herodiade, and that she paid homage to her, bowing her head and saying, ‘Be well, madonna Horiente’.” The Lady responded, “Welcome, my children.” Sibillia's testimony suggests peasant ceremonies seeking the blessings of a priestess representing a goddess, possibly initiating girls into womanhood by ceremonially presenting them to her. It may be that children were no longer admitted to pagan gatherings for fear that they would endanger their community by incautious disclosures to the wrong people.

Sibillia admitted that since her last arrest she had returned twice to the “games of Diana.” She said she was not able to attend the witches' society after she was made to throw a stone into a certain lake. (Animist tradition of the Pyrenees and Alps upheld a magical taboo against disturbing spirits of lakes, predicting that throwing stones into the water would arouse storms.) When inquisitors asked Sibillia whether she had spoken the name of god at the "games," she replied that no one would dare to do so in the presence of Oriente. [Bonomo, 16]

These pagan "games" appear to be of long standing. Boccaccio describes masquerades linked to the “wild hunt.” A masked giuoco del veglo ("game of the vigil") was outlawed around 1325. [Bonomo, 117] The Russian Rusalia is another example of a goddess festival colloquially referred to as the "games" (igrania), as the clergy's expostulations against it reveal. [Rybakov]The Inquisition also tried Pierina de' Bugatis twice for taking part in pagan rites. In her first interrogation, Pierina said that she had participated in the games of Diana, called Erodiade or Horiens. She and her followers went about like the dominae nocturnae (“ladies of the night”). They ate and drank at the houses of the rich and blessed houses that were clean and well-kept.

The living and dead took part in Oriente's assembly. This Goddess of the Witches possessed the power of life and regeneration. When her society ate animal flesh, they put the bones back in their skins. The goddess touched them with her magic wand, causing the animals to spring up alive. [Bonomo 17; Ginzberg II; both Ginzberg and Russell suggest that the name Oriente derived from the Her- or Ber-complex of names for the goddess who led the wild hunt. Russell, 333fn30, 49]

The Lady taught her company the nature of herbs and how to use them in healing. She answered their questions about illness, theft, and curses. Her responses always proved true. Oriente, said Pierina, was mistress of her society as christ was of the world; the christian god is never mentioned in her assemblies. Her account describes a pagan community, quite conscious of its vulnerability, which met secretly. No one should reveal to outsiders what took place in the assemblies. [Bonomo, 17]

Pierina too was admonished to repent after her first questioning and released. In the summer of 1390 the Milanese tribunal called her back. Her judges were more severe now that she had flouted their reprimands. Pierina's testimony in the second deposition changed dramatically. Her responses now sound like the confessions of later torture-trials. The transcript says that Pierina had been carried to the “games” by Lucifelus, that she had given her body to the devil, and that he had written this pact down in blood. [Bonomo, 60]

These figments bear the definitive stamp of the theologians, tailor-made for a charge of heretical sorcery. While yielding to the necessity to repeat them, Pierina tried to justify her participation in the forbidden “games.” She told the Inquisitors that she was first forced to attend in the place of an aunt who would otherwise have been unable to die without having found a replacement. [Bonomo, Evans] This mythical theme of the witch needing to pass on her witchcraft recurs often in early modern folklore over most of southern Europe.

In 1390 the Inquisition sentenced both Pierina and Sibillia to death as relapsed heretics. Others must have been tried and burned in the same time period, as inquisitorial method forced prisoners to name their confederates. What remains of these women's trial records suggests that they lived in a culture so steeped in goddess veneration that they did not bother to deny it to the inquisitors. The records also show that by the end of the 14th century those inquisitors had begun burning those who would not give it up.

The testimony of the Italian paisanas begins with the good women who go by night and their goddess with the ever-mutating name. She regenerates life, prophesies, teaches herbal medicine and protective magic. The quick and the dead attend her assemblies. Under pressure from the Inquisition, those caught worshipping her “confess” to dealing with the anti-god of the christians, the devil. These trials set a pattern that continued in the trials of folk healers over the next two centuries.

The theme of the goddess reviving the sacrificial cows also turns up in later witch trials. In 1474 people at Prato Avilio near Turin declared that the witches took fat cattle from farmers, slaughtered and feasted on them, then collected the bones and wrapped them in the hides. The cows leaped to life when they pronounced the words, "Sorge, Ronzola!" [Bonomo, 86; Lea, 503, has Canavese, 1500s, possibly another instance?] (The English equivalent would be “Get up, Bossie!”) Traditions of this restorative goddess of the witches seem to have been extremely farflung. As far away as Latvia, trial records say that witches sacrificed a cow to a female "earth demon," and that she restored it to life. [Pocs II, 27]

In Glamorganshire, the Welsh told the same story in a faery folk context. A farmer saw the Verry Volk slaughter his ox in a dream. After their feast, “they collected the hide and bone, except for one very small leg bone which they could not find, placed them in position, then stretched the hide over them; and as the farmer looked, the ox appeared as sound and fat as ever, but … it had a slight lameness in the leg lacking the missing bone.” In lower Bretagne, the same story was told of the local korrigans (faeries) or lutins (dwarves). They invite the farmer to feast on his own cow. “If he does so with good grace and humor, he finds his cow or ox perfectly whole in the morning, but if he refuses to join the feast or joins it unwillingly, in the morning he is likely to find his cow or ox actually dead and eaten.” [Wentz, 159]

Further trials of Italian women accused of pagan beliefs and rituals were held in the alpine communities of Como, Turino and Pignerol. Inquisitors in the southern Alps apparently began to persecute witches around 1360. In 1508 Bernardo Rategno, an inquisitor at Como, wrote that "the sect of the witches began to pullulate only within the last 150 years, as appears from the old records of trials by inquisitors, in the archives of our Inquisition at Como. [Tractatus de Strigiis, in Cohn, 145] That modern researchers have been unable to locate the records Rategno refers to does not prove that they did not exist. It simply underlines the fact that our original sources have been subject to destruction.

Other undocumented trials were going on in western Switzerland. The fanatical witch hunter Peter de Greyerz burned numerous witches in the vicinity of Berne from 1397 to 1406—that we know of. Accusations of baby-killing already figured in these trials. Persecutions were also under way in the northeastern province of Friuli, near the Austrian border, where witches were burned in 1399 at Portaguaro. [Hansen?]

Distinctions between elements of the old religion and paganized Catholicism had become blurred. Fragments of pagan cosmology were lost, others were revised and preserved under new names in old wives' tales. Churchly dualism severed them into categories approved and forbidden by the hierarchy. Saints' names displaced the old nomenclature of divinities and their local sanctuaries--or the people's goddesses were utterly cast out by the clergy as demons. Ideas preached in sermons and enforced by episcopal courts or Inquisitors began to make headway.

La Signora del Corso was reversed from a wise, life-giving goddess to an evil devil, increasingly portrayed as a male master of witches. The "good women" are no longer described as powerful beings who give out abundant life, growth, and fortune but as devil's slaves who curse and blast. The Tregenda and Walpurgisnacht flighst of witches and spirits were reworked along the same lines, along with the old stories of fadas and witches dancing on holy mountaintops. When the priesthood found that it had failed to suppress these witch traditions after centuries of campaigning against pagan culture, another tack was taken.

Demonologists saddled the witch tradition with their own fantasies of Satanism: the notion of devil-worship; cannibalism of stolen, unbaptised babies; and orgies of sex that was degrading and painful for the women. The Inquisitorial torture trial enforced and spread these delusions, and drove witches into hiding as neither the episcopal courts nor secular persecutions had been able to do. Fear of denunciation to the Inquisition had a chilling effect on shamanism, open observance of the old rites, and public ceremonial not led by priests. As these were forced underground, the animist goddess faith began to drift from its foundations.© 2000 Max Dashu. All rights reserved.

Articles | Home | Secret History of the Witches